System & File Artifacts

cat /etc/fstab provides more inside how the Linux box is set up. Noticeably, attackers may mount a particular path to RAM; hence, it will not survive upon reboot.

As an incident responder, it’s your responsibility to check if there is an unknown mount on your system, to check the mount present on your system, you can type: cat /proc/mounts !

Get the system environment details.

Run

envand save the output to a text file.

Find recently accessed/modified/changed files by a user with find:

The general process is the same as on Windows and the analysis of inode data is very valuable. The main point here is that there is a difference in how timestamps work. Windows has four timestamps in $STANDARD_INFO and four in $FILE_NAME. Most Linux environments have three – MAC – with EXT4 introducing a Born-on time to more closely resemble Windows. Modification Time, also referred to as mtime. This is the last time data was written to the file. Access Time, also referred to as atime. This is the last time the file was read. Change Time, also referred to as ctime. This is the last time the inode contents were written. Born-on time, also referred to as btime. EXT4 file systems also record the time the file was created.

Incident responders can use this to hunt across a file system to find things the attacker may have changed. For example, if you think an attack took place in the last week, you can run:

find / -mtime -7

_Example find command for files accessed/modified/changed by username in the last 7 days: find . -type f -atime -7 -printf “%AY%Am%Ad%AH%AM%AS %h/%s/%f\n” -user <username>|sort -n find . -type f -mtime -7 -printf “%TY%Tm%Td%TH%TM%TS %h — %s — %f\n” -user <username>|sort -n find . -type f -ctime -7 -printf “%CY%Cm%Cd%CH%CM%CS %h — %s — %f\n” -user <username>|sort -n

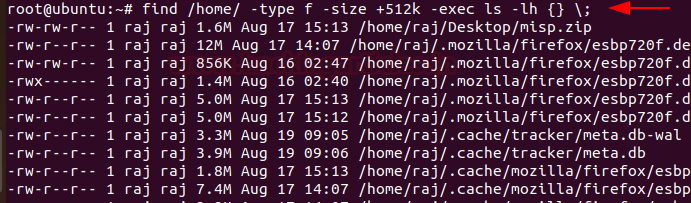

To identify any overly large files in your system and their permissions with their destination, you can use: find /home/ -type f -size +512k -exec ls -lh {} \;

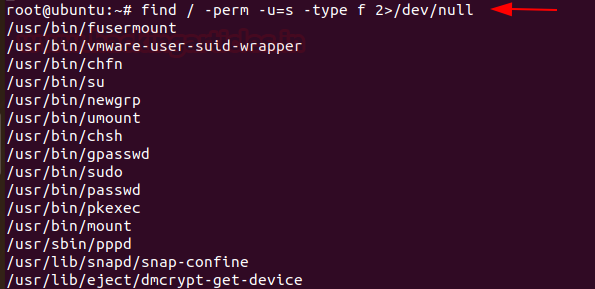

Whenever any command runs, at which SUID bit is set then its effective UID becomes the owner of that file. So, if you want to find all those files that hold the SUID bit then it can be retrieved by typing the command

find /etc/ -readable -type f 2>/dev/null

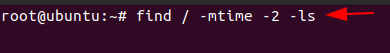

As an incident responder, if you want to see an anomalous file that has been present in the system for 2 days, you can use the command,

find / -mtime -2 -ls

VimInfo File: /home/username/viminfo would review a lot of information about opened files, search string, command lines and epoch time.

To check for SUID bit, which allows programs to be executed with root privileges: find / -perm -04000

Another command-line tool we can use is the id command. The id command shows both the user’s ID and the groups they are members of:

Here is what we have:

uid=1000 shows the user’s unique identifier (UID)

gid=1000 indicates the user’s primary group identifier (GID)

groups=1000(eric),4(adm),24(cdrom),27(sudo),30(dip),46(plugdev),116(lpadmin) displays all the groups that the user belongs to. Each group is represented by its GID, and its name is shown in parentheses. As we can see, the user eric belongs to several groups, including adm, cdrom, sudo, dip, plugdev, and lpadmin.

Directory names starting with .: This is a technique to try and hide entire directories where the attacker can store tools/data.

Regular files in /dev: The /dev folder should hold devices. If you find any regular files in there its worth a closer look.

find / -perm -4000 2>/dev/null Check for binaries with SUID bit set. And if anything unexpected appears it is worth investigating

If your system uses a package management tool, you should check to see if anything is different from the “official” version. Changes should be considered for investigation.

find / -nouser -print - Find files with no user.

/Var/Log

/var/log/syslog or /var/log/messages: Shows general messages and info regarding the system. Basically a data log of all activity throughout the global system. Know that everything that happens on Redhat-based systems, like CentOS or Rhel, will go in messages. Whereas for Ubuntu and other Debian systems, they go in Syslog.

/var/log/auth.log or /var/log/secure: Keep authentication logs for both successful or failed logins, and authentication processes. Storage depends on system type. For Debian/Ubuntu, look in /var/log/auth.log. For Redhat/CentOS, go to /var/log/secure.

cat /var/log/secure | grep "authentication failure" cat /var/log/secure | grep "users NOT in sudoers" cat /var/log/secure | grep "lock"

/var/log/boot.log: start-up messages and boot info.

/var/log/maillog or var/log/mail.log: is for mail server logs, handy for postfix, smtpd, or email-related services info running on your server.

/var/log/kern: keeps in Kernel logs and warning info. Also useful to fix problems with custom kernels.

/var/log/dmesg: a repository for device driver messages. Use dmesg to see messages in this file.

/var/log/faillog: records info on failed logins. Hence, handy for examining potential security breaches like login credential hacks and brute-force attacks.

/var/log/cron: OR /var/log/cron.log :keeps a record of Crond-related messages (cron jobs). Like when the cron daemon started a job.

Eg: One of the security audits is to look for failed authorizations in the cron service logs.

cat /var/log/cron | egrep 'FAIL|ERROR'

/var/log/daemon.log: keeps track of running background services but doesn’t represent them graphically.

/var/log/btmp: keeps a note of all failed login attempts.

/var/log/utmp: current login state by user.

/var/log/wtmp: record of each login/logout.

/var/log/lastlog: holds every user’s last login. A binary file you can read via lastlog command.

lastlog -u mytestuser/var/log/yum.log: holds data on any package installations that used the yum command. So you can check if all went well.

/var/log/httpd/: a directory containing error_log and access_log files of the Apache httpd daemon. Every error that httpd comes across is kept in the error_log file. Think of memory problems and other system-related errors. access_log logs all requests which come in via HTTP.

/var/log/mysqld.log or /var/log/mysql.log : MySQL log file that records every debug, failure and success message, including starting, stopping and restarting of MySQL daemon mysqld. The system decides on the directory. RedHat, CentOS, Fedora, and other RedHat-based systems use /var/log/mariadb/mariadb.log. However, Debian/Ubuntu use /var/log/mysql/error.log directory.

/var/log/pureftp.log: monitors for FTP connections using the pureftp process. Find data on every connection, FTP login, and authentication failure here.

/var/log/spooler: Usually contains nothing, except rare messages from USENET.

/var/log/xferlog: keeps FTP file transfer sessions. Includes info like file names and user-initiated FTP transfers.

/var/log/kern.log- Show kernel log

cat -f /var/log/wtmp saves successful login logs

cat -f /var/log/btmp saves successful login logs

Now, I will read authentication logs to see the details of users logged in along with other information. cat var/log/auth.log

![]()

cat /var/log/syslog OR syslog.*

It shows each instance of user login and logouts, how long the session was active for, and which host the connection came from. last -aiF

Last updated